I’ll go blind or lose a leg if I don’t take care of my diabetes: that’s the one lesson I feel I took away from information given to me when I was diagnosed in 1997, just prior to my 9th birthday.

It’s all quite a blur but I remember those warnings. I remember feeling small and not understanding what I had done to deserve it, why me? Feelings of insecurity, self-doubt and hatred that would later fuel the beginning of my eating disordered behaviours had already started to simmer away in the background. For a long time I was in a state of denial, a little of which still remains in me. I used to pretend I wasn't any different to anyone else.

Language matters. Certain remarks are always remembered: I can vividly recall attending my diabetic clinic appointment at the age of 14 and just prior to the emergence of anorexia. I was at the upper limit of the healthy BMI range and my endocrinologist told me to be careful not to put on any more weight and that losing a few pounds would probably be beneficial to me. The next time I saw that doctor he congratulated me on the far lower number on the scale. He’ll have had no clue whatsoever as to how those words stuck with me and made me so fearful of becoming fat as I started to starve and shrink.

It seems that care has improved quite significantly for children diagnosed with diabetes these days, and the structure of treatment has changed: We no longer have to take set amounts of insulin and so stick to a regular, proportioned diet. Instead the basal and bolus routine means we can adjust our doses and take the right amounts needed to cover any kind of food we want to eat. Advances in technology such as pumps and CGM’s provide even more flexibility and some freedom from feeling so much like a pin cushion. But the rhetoric of blame and guilt for having diabetes and furthermore, the complications it causes is still put onto us. Most of all by the media and carried by members of the public that consume those headlines and read or hear inaccurate reporting regarding diabetes and so just don't know any better. The diabetes community which is most active within the social media sphere is fully informed and yet the ignorance that falls outside of that is still damaging and hurtful.

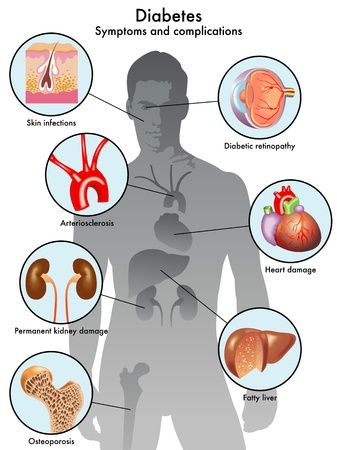

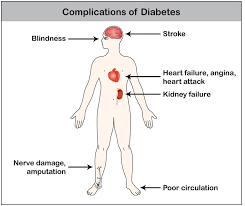

I see a lot of coverage of the potential complications of type 1 diabetes, even from charities and such that do it in a sensitive manner, but still I don’t see too much out there on management of them, advice on how to cope with additional chronic conditions in both a physical and mental sense. This is important and there needs to be guidance and resources available.

DWED are in fact in the midst of the production of a series of content packages which highlight on 4 separate common complications – these materials are available to our members. We have covered retinopathy, gastroparesis, and neuropathy so far and next we are moving on to nephropathy. For this I have interviewed a number of people with T1ED as case studies who also have direct experience of these complications. Common themes have emerged which also mirror my own history: shame, embarrassment, frustration at the false assumptions that other people around you may make. But also there’s hope, there’s perseverance and bravery.

Still, it can be too simple to think you are invincible and don’t need to worry about any of the longer term ramifications, not just yet. You aren’t at your goal weight yet. You’ll totally stop this stupidity after you’ve made it there. You’ll recover and graduate and be in your chosen career - you’ll be a proper adult, right? But months tumble into each other and then into years. You look back and think ‘damn, I really didn’t mean to do this.’

With complications you can feel totally safe until the **** hits the fan. Sorry, no way else I could put that! You don’t ever know when or what will come first, everyone with type-1-diabetes is different. Every time a new issue crops up I still feel like I am making a big deal and using up valuable appointment slots that could be used for other people. Again, that’s the sneaky self destruction in me. I know it too, but that doesn’t seem to make it any weaker.

I think that for people who also have an eating disorder the onset of complications often seems to come alongside a sense of fault and failure. Failure for being unable to control and cope with diabetes in the way they “should” do and putting themselves at risk through insulin restriction for weight loss purposes (“Diabulimia”) or/and the more ‘typical’ disordered eating behaviours such as purging by vomiting or cutting down food intake and calories [T1-ED].

T1ED can stamp you down with a double dose of guilt. Despite what other people may think about diabetes and the misinformed judgements they might make, anyone that lives it knows the real facts, eating disorder or otherwise: That type 1 diabetes is not caused by poor lifestyle choices, and cannot be reversed or prevented. Yet, what about the complications it may lead to? You can never be certain as to when they may have developed and whether your eating disorder means you are experiencing them at an earlier rate. Honestly, I’d guess from hearing other people’s experiences, for most it will be a definite contributing factor. For that you might feel real, raw guilt, guilt that feels more justifiable in comparison to the irrational-that-you-know-is-irrational Type 1 Diabetes guilt.

But is it, really?

An eating disorder is a mental illness and can feel all consuming. In the beginning you don’t think of the future, of still being ill in ten years time. Of having to deal with neuropathic pain and frequent laser eye sessions, a stomach that doesn’t work properly and can lead to quite unpleasant effects, far from glamorous or just that little thinner and fitter, like you intended to be. You don’t even consider that you might have to someday walk with an aid and not be able to go far on your own. But this is the truth of it, and I am merely glossing the surface. An eating disorder is sneaky, deceptive and can prevent the ability to seeing any kind of wider perspective Your world revolves around food and numbers and secrets, avoided diabetes clinic and nurse appointments, pretending you’ve taken insulin or eaten, or not eaten (after binging), lies that fall out your mouth with added embellishment for authenticities sake. It can make you feel completely powerless.

Confirmed diagnosis of complications may help or hinder someone attempting recovery from an eating disorder/T1ED or Diabulimia. It may feel they have been given a concrete reason that they need to try to take better care of themselves and so reduce further risk. On the flip side it is common to feel defeated and damaged beyond repair. From a fast moving car you look out the passenger seat and lose yourself in your own heads, until your body becomes so tired and the dissociation begins to lift – you notice the trees, grass. The breeze against your face and realise that none of it was ever worth it. You climb into the driver’s seat and try to steer but nothing is familiar. You want to stop and breathe but you realise the brakes are faulty; you’ll survive mostly unscathed after crashing the car against a safety barrier.

Nobody means to end up with a list of complications that for some reason seem to all hit at once like falling dominoes. Take me: coincidentally I’ve had a horrendous week with neuropathy, quite possibly due to medication changes. On Friday my balance was so compromised that I couldn’t walk in a straight line or hold myself up, and the pain felt unbearable – numbness and pain consecutively which seems like a contradiction but you’ll know exactly what I mean if you’ve been there. Next thing was on Tuesday I noticed another black ‘floater’ in my left field of vision so have an emergency eye clinic tomorrow.

I can’t really say how it makes me feel. I’ve had retinopathy for a while and three laser surgery sessions, but I’d ever been through neuropathy to the degree where it left me pretty much incapacitated. I did feel momentarily scared, when it was happening and my balance was totally off kilter, but that floated away and I am left with numbness, a whole lot of nothing, to a degree where I am almost nonchalant about it all.

The main element I wanted to bring into this is the effectiveness (or not) of “shock tactics.” I have recently concluded that I am pretty much immune to them. I think this is for two reasons: the first is because I have trouble giving a damn about myself – all that mental health head crap. The second I feel may be relevant to other with type 1 diabetes that were also told the horror stories growing up of losing legs and eyesight and even becoming bedbound. Some like me may have heard such horror stories numerous times over., thrown at you during another attempt to give you a 'wake up call'. It all gets a bit old. It perpetuates the isolation we already feel from the people around us without type 1 diabetes.

We know all the risks without even reading sensationalist ‘real life’ type stories. We are the experts of our own condition. Personally, nothing anyone could say to me in terms of possible dangers of mismanaging my insulinr would ever faze me.

This is something I wish my family and some friends could accept. I KNOW it comes from a place of care, but the things they can say to try and jolt me out the eating disorder I’ve had for over half my life, and make me face up to what I am doing to myself. I don’t need that. It doesn’t help, and it can actually hurt. Instead I need to be listened to and be able to rant about type-1- diabetes, about neuropathy keeping me awake at night and blurred vision that means I have difficulty reading some labels. Being told I brought this on myself just makes me want to withdraw and beat myself up inside a little more. The bottom line is that shock tactics have no influence on me beyond causing upset. Too many lectures over the years have worn me down and people should save their breath.

I’d be interested to know if this immunity to ‘scare tactics’ is a trait many other type 1’s feel they have. Do you suddenly ‘wake up’ and tighten your monitoring and dosing accordingly if you develop signs of complications? Furthermore, if people tell you that you might need amputation one day or lose your sight is it effective in causing you to act and try to regulate your sugar levels? Or is it support and an acknowledgement that you are doing your best to get through the days that is more useful in helping you to start making changes? I wonder if this is different for people with T1ED due to the influence of how we feel about ourselves.

The names of diabetes complications are not even of use, really. It’s the impact they have on us and our general quality of life that counts. Burying our heads in the sand is no use, but still, there is no need to catastrophise. Complications may not be completely cured but they can be treated. Health Professionals have the means to try and stop progression with medications, changes to diet for gastroparesis and procedures for retinopathy ranging from laser eye surgery to vitrectomy surgery.

Complications are not a death sentence or burdens weighing us down. Every single person I interviewed on the subject was surviving despite really tough circumstances. Type 1 diabetics are the strongest people I know and stronger more for dealing with such life altering complications. We keep going and even on low days, we don’t give in. We hold each other up if we need to and remind each other that guilt and blame has no place. Dwelling on what might have been is futile.